I speak French, albeit poorly. I studied it for years, used it while traveling, and can still navigate a menu without pointing. But if a French-speaking client walked through my door asking for help clarifying his message, the session would struggle from the start. Not because the principles of clarity change across languages, but because every sentence would require translation in my head.

That translation is friction. And friction cannot be eliminated by adding more words.

This is where most business owners make their first mistake. When a message fails to land, they assume the solution is explanation. They add detail. They clarify further. They repeat themselves in slightly different terms. What they’re actually doing is increasing the translation load, asking the listener to work harder to interpret meaning that was never native to them in the first place.

I see this constantly in consulting calls. A founder describes what they do, and I don’t understand. They notice my confusion and immediately launch into more detail—more features, more benefits, more context. Five minutes later, I’m further from understanding than I was at the beginning. The problem was never insufficient information. The problem was that we weren’t speaking the same conceptual language, and more words in the wrong language only deepens the confusion.

Translation kills clarity.

When you speak your native language—conceptually, not just linguistically—you don’t translate. Neither does your listener. Meaning moves directly from one mind to another without resistance. Something important happens in that moment: you naturally attract people who think the same way you do.

This is why clarity is not about appealing to everyone. It’s about resonance, not reach. When you speak in your own language, you stop convincing and start aligning. The wrong people self-select out. The right people lean in. That’s not a marketing tactic. It’s a structural truth.

Most people resist this idea because it feels limiting. If I narrow my language, won’t I narrow my market? The opposite is true. Broad language doesn’t expand your audience; it dilutes your message until no one hears it clearly. Precision creates pull. Vagueness creates hesitation.

But shared language alone is not enough.

Clarity also has grammar.

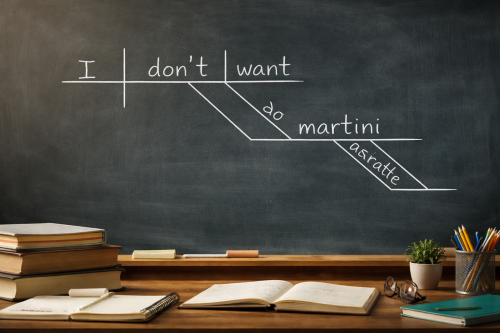

Even when two people use the same words from the same dictionary, meaning can collapse if the structure is wrong. Grammar determines function. Order determines intent. A single shift can invert the message entirely.

“Don’t I want a martini?” and “I don’t want a martini” use identical words. One is questioning desire. The other is declining an offer. Rearrange the order, and the meaning shifts completely. The vocabulary hasn’t changed, but the outcome has.

This happens in business communication constantly. A consultant sends a proposal that reads: “We help companies struggling with operational inefficiency improve their processes.” Rearrange it slightly: “We improve operational processes for companies ready to scale.” Same service. Different grammar. The first implies the client is broken. The second implies the client is ambitious. One repels. One attracts.

This is what most people miss about communication. Vocabulary creates familiarity. Grammar creates meaning. Ignore the rules, and you can say the opposite of what you intend while believing you’ve been perfectly clear.

If a financial advisor came to me saying, “I help people who don’t know what to do with their money,” I’d stop him immediately. He might think he’s being inclusive. What his prospects hear is, “I work with people who are clueless.” The words are technically accurate. The grammar is disqualifying. Change it to, “I work with people who have built something and aren’t sure of the best way to protect it,” and he could probably double his closing rate. Same audience. Different structure. Completely different outcome.

Clarity fails long before presentation, copy, or delivery. It fails when we speak to the wrong audience, in the wrong language, with the wrong structure—and then attempt to fix the problem by talking more.

True clarity begins earlier. It begins with selection. Who are you speaking to? What language do they already think in? And do you understand the grammar that governs how meaning works in that world?

When those elements align, clarity doesn’t need to be forced. It happens naturally. Decisions feel obvious. Conversations feel efficient. Outcomes feel earned rather than coerced.

Clarity is not something you add at the end. It’s something you choose at the beginning.